Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(8):501-506

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliation.

Peritonsillar abscess is the most common deep infection of the head and neck, occurring primarily in young adults. Diagnosis is usually made on the basis of clinical presentation and examination. Symptoms and findings generally include fever, sore throat, dysphagia, trismus, and a “hot potato” voice. Drainage of the abscess, antibiotic therapy, and supportive therapy for maintaining hydration and pain control are the cornerstones of treatment. Most patients can be managed in the outpatient setting. Peritonsillar abscesses are polymicrobial infections, and antibiotics effective against group A streptococcus and oral anaerobes should be first-line therapy. Corticosteroids may be helpful in reducing symptoms and speeding recovery. Promptly recognizing the infection and initiating therapy are important to avoid potentially serious complications, such as airway obstruction, aspiration, or extension of infection into deep neck tissues. Patients with peritonsillar abscess are usually first encountered in the primary care outpatient setting or in the emergency department. Family physicians with appropriate training and experience can diagnose and treat most patients with peritonsillar abscess.

Peritonsillar abscess is the most common deep infection of the head and neck, with an annual incidence of 30 cases per 100,000 persons in the United States. 1 – 3 This infection can occur in all age groups, but the highest incidence occurs in adults 20 to 40 years of age. 1 , 2 Peritonsillar abscess is most commonly a complication of streptococcal tonsillitis; however, a definitive correlation between the two conditions has not been documented. 4

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Some type of drainage procedure is appropriate treatment for most patients who present with a peritonsillar abscess. | C | 6 , 7 , 13 |

| Broad-spectrum antibiotics effective against group A streptococcus and oral anaerobes should be considered first line after drainage of the abscess, although some evidence suggests that penicillin alone may be sufficient. | C | 9 , 12 , 17 , 18 |

| Corticosteroids may be useful in reducing symptoms and speeding recovery in patients with peritonsillar abscess. | B | 3 , 15 , 26 |

The two palatine tonsils lie on the lateral walls of the oropharynx in the depression between the anterior tonsillar pillar (palatoglossal arch) and the posterior tonsillar pillar (palatopharyngeal arch). The tonsils are formed during the last months of gestation and grow irregularly, reaching their largest size by the time a child is six to seven years of age. The tonsils typically begin to involute gradually at puberty, and after 65 years of age, little tonsillar tissue remains. 5 Each tonsil has a number of crypts on its surface and is surrounded by a capsule between it and the adjacent constrictor muscle through which blood vessels and nerves pass. Peritonsillar abscess is a localized infection where pus accumulates between the fibrous capsule of the tonsil and the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle. 6 , 7

Peritonsillar abscess has traditionally been regarded as the last stage of a continuum that begins as an acute exudative tonsillitis, which progresses to a cellulitis and eventually abscess formation. However, this assumes a close association between peritonsillar abscess and streptococcal tonsillitis. Because the occurrence of peritonsillar abscess is evenly distributed throughout the year and streptococcal tonsillitis is generally seasonal, the role of streptococcal tonsillitis in the etiology of peritonsillar abscess has been called into question. 8

Abscess formation may not originate in the tonsils themselves. Some theories suggest that Weber glands contribute to the formation of peritonsillar abscesses. 4 , 9 This group of minor mucous salivary glands is located in the space just superior to the tonsil in the soft palate and is connected by a duct to the surface of the tonsil. 9 These glands clear the tonsillar area of debris and assist with digesting food particles trapped in the tonsillar crypts. If Weber glands become inflamed, local cellulitis can develop. As the infection progresses, the duct to the surface of the tonsil becomes obstructed from surrounding inflammation. The resulting tissue necrosis and pus formation produces the classic signs and symptoms of peritonsillar abscess. 4 , 9 These abscesses are generally formed within the soft palate, just above the superior pole of the tonsil, which coincides with the typical location of a peritonsillar abscess. 4 The lack of these abscesses in patients who have undergone tonsillectomy supports the theory that Weber glands may contribute to the pathogenesis of peritonsillar abscesses. 4 Other clinical variables associated with the formation of peritonsillar abscesses include significant periodontal disease and smoking. 10

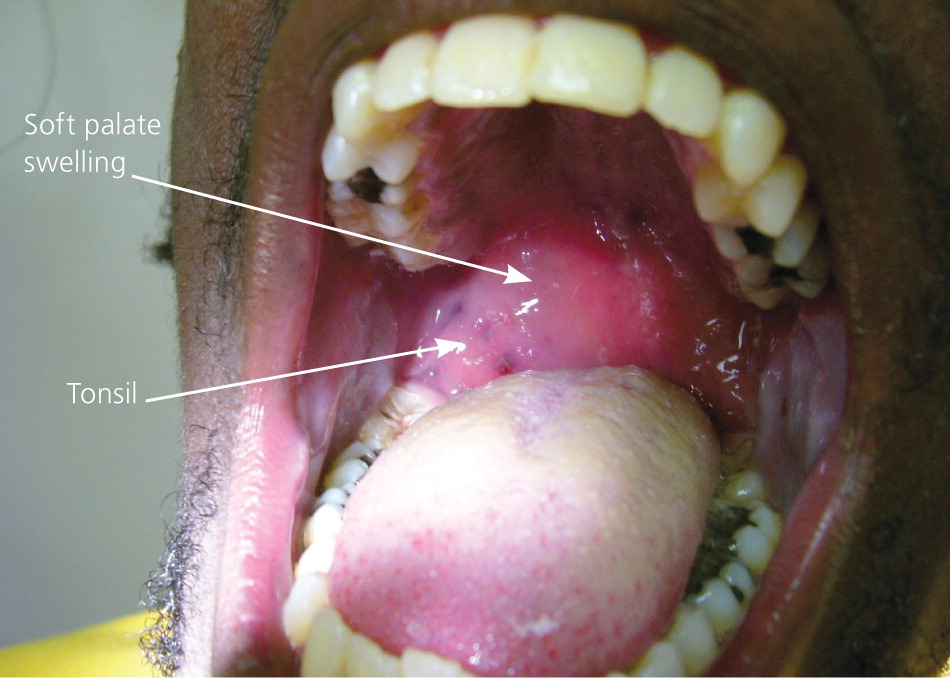

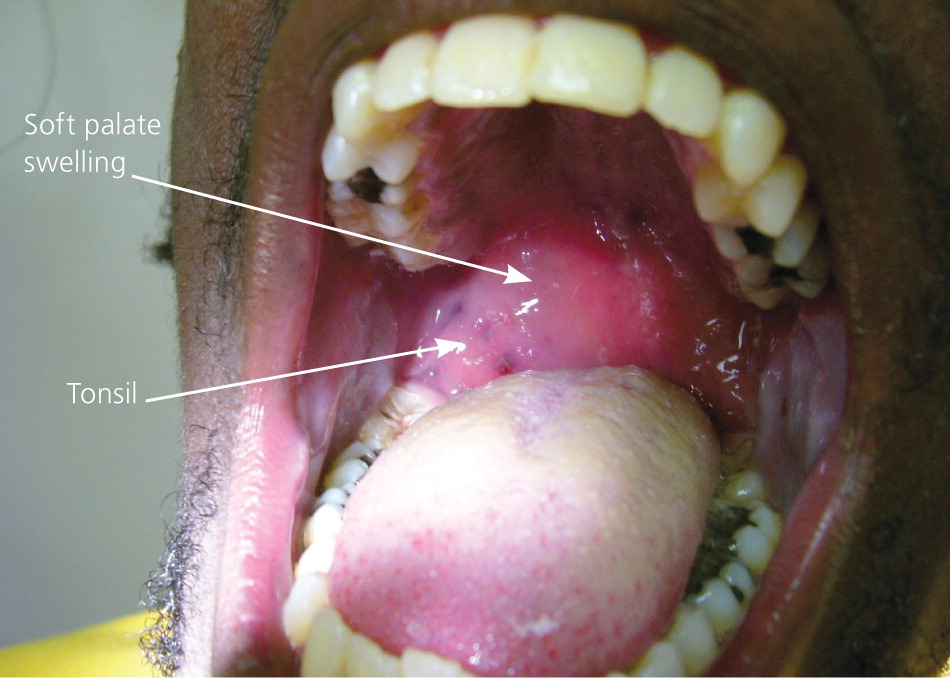

Patients with peritonsillar abscess appear ill and report malaise, fever, progressively worsening throat pain, and dysphagia. 7 The associated sore throat is markedly more severe on the affected side and is often referred to the ear on the ipsilateral side. Physical examination usually reveals trismus, with difficulty opening the mouth secondary to inflammation and spasm of masticator muscles. 11 Swallowing can be difficult and painful. 11 , 12 The combination of odynophagia and dysphagia often leads to the pooling of saliva and subsequent drooling. Patients often speak in a muffled or “hot potato” voice. Marked tender cervical lymphadenitis may be palpated on the affected side. Inspection of the oropharynx reveals tense swelling and erythema of the anterior tonsillar pillar and soft palate overlying the infected tonsil. The tonsil is generally displaced inferiorly and medially with contralateral deviation of the uvula 11 (Figure 1 1 ).

The most common history and physical examination findings in patients with peritonsillar abscess are summarized in Table 1. 4 , 7 , 11 , 12 Potential complications of peritonsillar abscess are outlined in Table 2. 13 If it is inadequately treated, life-threatening complications can occur from upper airway obstruction, abscess rupture with aspiration of pus, or further extension of the infection into the deep tissues of the neck, putting neurologic and vascular structures at risk. 7 , 13

| Symptoms |

| Dysphagia |

| Fever |

| Malaise |

| Odynophagia |

| Otalgia (ipsilateral) |

| Severe sore throat, worse on one side |

| Physical examination findings |

| Cervical lymphadenitis |

| Drooling |

| Erythematous, swollen soft palate with uvula deviation to contralateral side and enlarged tonsil |

| Muffled voice (“hot potato” voice) |

| Rancid or foul-smelling breath (fetor) |

| Trismus |

| Airway obstruction |

| Aspiration pneumonitis or lung abscess secondary to peritonsillar abscess rupture |

| Extension of infection into the deep tissues of the neck or superior mediastinum |

| Life-threatening hemorrhage secondary to erosion or septic necrosis into carotid sheath |

| Poststreptococcal sequelae, such as glomerulonephritis and rheumatic fever, when infection is caused by group A Streptococcus |